The Rewards of Risk-Aware Investing: What is your risk premium?

Over the last three years, the S&P Index has increased by approximately 80 percent. During this period, the S&P Index has not suffered a decline of 10 percent or more - something that has historically occurred about once a year.

This exceptional performance has led many popular financial media sources to share their caution about the potential for a market correction. As we approach the sixth year of a bull market, this is an opportune time for investors to review a few basic principles of portfolio composition to help develop an asset allocation they can confidently rely on no matter what the market may bring.

Investment portfolios today are generally constructed in two stages. In the first stage, a determination is made to allocate investor resources across various asset classes. Ideally, this exercise objectively assigns amounts to different asset classes based on the particular goals, objectives, and risk tolerance of the investor. The mix of assets designated relies on empirical analysis of historical asset class returns and how they are expected to perform relative to one another throughout various market cycles. After the allocation decisions are finalized, the next stage involves the actual selection of investment managers and/or funds to obtain the desired exposure to the various asset classes determined during the first stage. From this point forward, periodic performance reviews and rebalancing the mix of asset classes are essential to help keep the portfolio in alignment with the investor’s specific objectives.

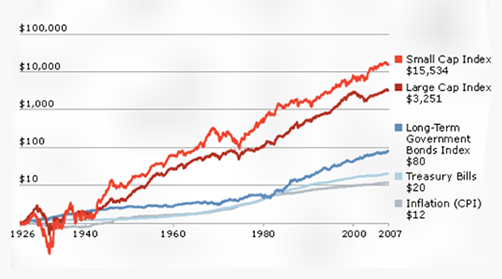

Accepting uncertainty is inevitable in this process. Investors must be willing to accept a given level of risk in order to obtain returns that exceed those of “risk-free” asset alternatives such as money market funds and bank deposits. History has indeed proven this to be worthwhile, as over long enough periods of time, riskier assets like stocks have generally outperformed safer assets like bonds (see table below). The amount of excess return an investor expects over the risk-free rate of return is known as the “risk premium” and, as the term implies, does not come without a cost. Riskier assets are generally more volatile and may be subject to periods of extreme short-term fluctuation. Being keenly aware of the various uncertainties in a portfolio is very important for investors since risk is both a key component in the allocation process as well as a factor in evaluating performance.

Long-Run Returns by Asset Class

There are two main categories of investment risk. “Systematic risk”, also referred to as “market risk” or “un-diversifiable risk”, is the risk resulting from being invested in the broad market, asset class, or industry. Some asset classes are inherently more volatile and carry more systematic risk than other asset classes. Conversely, “unsystematic risk” (a.k.a, “specific risk” or “diversifiable risk”), is based on company-specific traits. For example, news about a strike at a company will likely impact that company’s stock price more than the broader market.

Modern portfolio theory is based on the fact that investors care about both risk and expected return. Since various asset classes are not perfectly correlated with one another, diversification should allow for each of the following:

- For a given level of expected return, there exists a minimum level of risk necessary to achieve that level of expected return.

- For a given level of risk accepted, there exists a maximum level of expected return achievable.

If investors chose only to account for systematic risks, the portfolio chosen could be implemented with a selection of index funds and/or exchange traded funds from each of the various asset classes, since these are composed of a significant amount of underlying positions that essentially diversify away the unsystematic (i.e. company-specific) risks. However, if a specific manager or fund could be identified in one or more asset classes that could consistently outperform their benchmark index after accounting for fees, the investor might choose to use such an actively managed approach. Viewed in this light, active managers and funds should only be utilized if the investor believes they have the ability to outperform their benchmark after fees over the investment horizon.

The graph shown above clearly illustrates that investors have been generally rewarded for accepting risk over long periods of time. Inexperienced investors might draw the conclusion that taking on more risk in a portfolio will lead to a higher expected return. More astute investors never disregard the understanding that taking risk may subject a portfolio to shorter-term fluctuations that can have unfavorable consequences.

To best prepare for whatever the markets and characteristics of their specific investments may bring them, investors must carefully construct portfolios with an awareness of the various types and levels of risks they are willing to accept and be certain that they are being fairly compensated for doing so. The portfolio should also be evaluated periodically to analyze how the portfolio as a whole as well as each contributing component has fared against appropriate benchmarks and anticipated uncertainties. The most effective performance reviews will also be accompanied with a determination of whether any rebalancing of the asset mix is appropriate. During periods of increased market volatility and while considering any changes to manager and/or fund selections, the importance for this type of analysis and review only increases. The process of allocating investment resources requires careful diligence, but the result should be long-term expected rewards.